On the steps of the 261-year-old edifice — once at the heart of the American political story, erected with funds from the slave trade — the protestors called on the University to dismantle its institutional racism.

Their demands included the creation of affinity housing and spaces for Black students, cultural competency training for faculty, an undergraduate distribution requirement dedicated to the history of marginalized peoples, and the removal of Woodrow Wilson Class of 1879’s name from the policy school and residential college.

With their list in hand, the students entered the Nassau Hall office of President Christopher Eisgruber ’83. Organizers passed around a sign-up sheet for students to sit in Eisgruber’s office during his work hours through the week — or until he committed to pursue their demands.

“It was technically [Eisgruber’s] office hours,” former BJL member Destiny Crockett ’17 recalled.

Around noon, Eisgruber came into his office and began to speak with the protestors. Leaning against his desk, he addressed the students, who sat on the floor around his meeting table, surrounding his feet.

According to former BJL member Trust Kupupika ’17, Eisgruber questioned what could be “properly defined as racist,” especially with regard to mandatory cultural competency training, which he viewed as “neither feasible nor effective.”

As Nassau Hall’s closing time, 5:30 p.m., approached, students began to consider whether to spend the night.

“People who were in the office were informed that if they were to leave, then PSafe would not allow them to return the next day,” Kupupika said.

“Someone brought sleeping bags, toothbrushes, toothpaste and deodorant,” Crockett said. Outdoor protesters began to set up tents, preparing for rain.

At 5:15 p.m., Dean of Undergraduate Students Kathleen Deignan came to Eisgruber’s office with a warning to student protesters.

“You should anticipate that there could be disciplinary consequences when students occupy private space,” she said. “No one can remain in the building after the building closes.”

Student protestors set up tents outside Nassau Hall.

Courtesy of University Press Club live-blog

Dinner in Nassau Hall during the BJL’s protest. Supporters of the protests provided food.

Courtesy of University Press Club live-blog

Joanna Anyanwu ’15 GS and Crockett, who were in the room at the time, told The Daily Princetonian they feared expulsion and weighed whether they should leave. Anyanwu called her mother, whose advice was straightforward: “Don’t get expelled.”

Crockett stayed in the office, but Anyanwu decided to sleep outside.

Outdoors, students sang and chanted. Many, including Kupupika, marched down campus to the residential college that bore Wilson’s name. Others stayed outside Nassau Hall, so that they could be heard by those sitting in. A steady rain fell.

◆

The next morning, the rain stopped, the sun rose, and students awoke after a night spent on atrium tile, office carpet, and the ground outside.

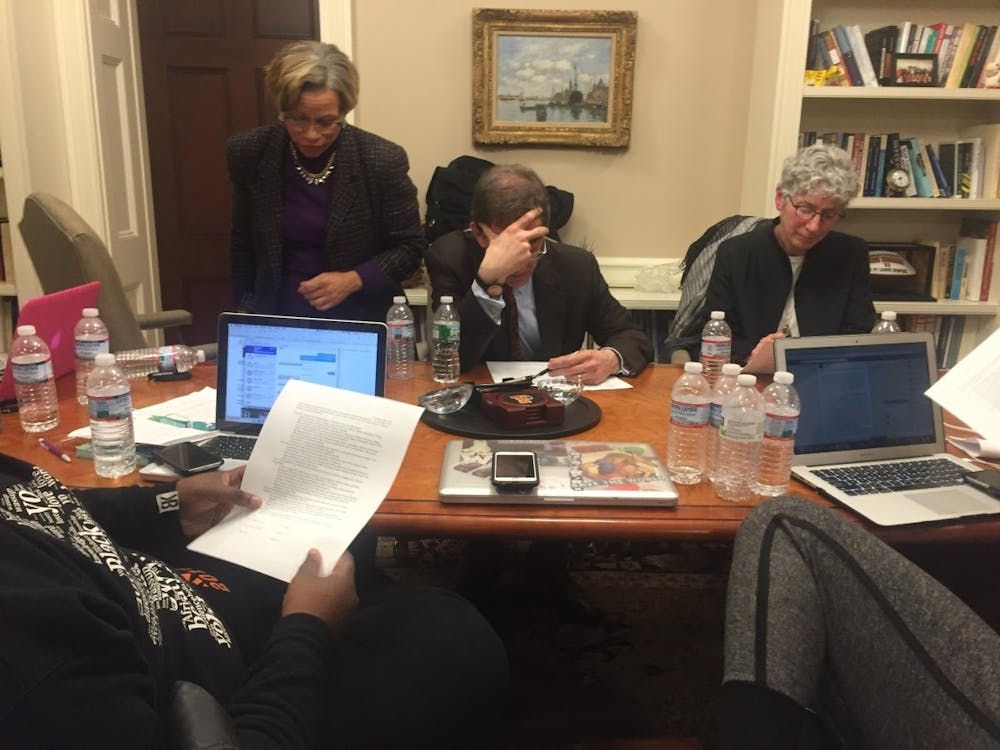

By 2 p.m., Eisgruber, Dolan, and other administrators agreed to meet the sit-in protesters. What followed was a six-hour back-and-forth.

Once again, nighttime arrived, with no resolution in sight. Protestors and administrators began to draft a revised sheet of demands for University representatives to sign. As the discussion reached an impasse, chants from the atrium resonated in the office.

“No Justice, No Peace. No Justice, No Peace.”

Students both within and outside of Nassau Hall prepared their makeshift beds for a second night’s sleep, but after the students granted a last-minute concession, Eisgruber agreed to sign their revised demands.

At 8:45 p.m., Nov. 19, sit-in protesters stepped outside of Nassau Hall for the first time in 33 hours. The sit-in was over, and they felt real change was in the air.

The victory was short-lived. At 9:05 p.m., as sit-in protesters were walking back to their dorms, they learned that a bomb and firearm threat had been made on Nassau Hall, making specific reference to the sit-in.

Fearing for her safety, Crockett reached out to Professor Emeritus Cornel West GS ’80 and Professor Imani Perry in the Department of African American Studies to ask if they could help arrange accommodations off campus.

Her faculty confidants first advised her to ask the University about what she could do. Crockett contacted an administrator who, she recalled, told her she need not be concerned.

Crockett returned to Professors Perry and West. That night, several BJL protesters stayed at the Nassau Inn on the professors’ dime.

◆

As the protest drew attention on campus and across the nation, the BJL garnered both support and backlash. In the months that followed, there would be little resolution.

Nov. 18, 2015

Students “walkout and speakout,” occupy Nassau Hall until demands of Black Justice League are met

Nov. 19, 2015

BJL protest targeted in bomb and firearm threat

Nov. 21, 2015

BJL sit-in countered by petition opposing their demands

Every member of the BJL has since graduated, and the organization no longer exists. But this year, the BJL reemerged in campus discourse, especially after the University met its demand for the removal of Wilson’s name in June.

Robertson Hall, which houses the Princeton School of Public and International Affairs (formerly the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs). Jon Ort / The Daily Princetonian

Yet, for BJL alumni who spoke with the ‘Prince,’ the Nassau Hall sit-in was never just a call to rename the School of Public and International Affairs. “Removing Woodrow Wilson’s name was not our first demand. It was not our fourth demand,” Anyanwu recalled.

Over the summer, BJL alumni criticized the renaming. “Such symbolic gestures — absent a more substantive reckoning with lasting traditions perpetuating anti-blackness that our full list of demands addressed — reflect the University’s ongoing failure to confront deep-rooted issues that allow the racist status quo to remain intact under the guise of progress,” they wrote.

“Six years after founding BJL and five years after our historic sit-in,” they continued, “we recognize that there are some demands we no longer find conducive to the project of Black liberation — such as diversity training — but we still believe Princeton must offer more than it has offered.”

They now share their experiences, ideas, and advice with current student activists, resolved not to let the demands and needs of Black students be indefinitely deferred or forgotten.

“A lot of the demands we made in 2015 were not new,” Anyanwu said. “They were made as early as the ’90s. They were made as early as the ’60s.”

In the words of Ella Jo Baker — the civil rights era icon whose footsteps the BJL sought to follow — “the struggle is eternal.”

“The tribe increases,” Baker continued. “Somebody else carries on.”

Five years after the Nassau Hall sit-in, BJL alumni, and the younger students they inspire, seek to do just that. ◆

To read more about the protests and their aftermath, see “‘Committee, committee, committee’: After five years, Princeton’s approach to institutional reform hasn’t changed,” by Ellen Li and Alex Gjaja, as well as “‘Resurfacing history’: A look back at the Black Justice League’s campus activism,” by Ellen Li and Omar Farah

Web design and development by Ananya Grover and Kenny Peng. Text written by Ellen Li and Omar Farah, and adapted by Jon Ort. Additional production by Alex Gjaja and Rachel Sturley. Copy-edited by Celia Buchband.